Interview with MAKOTO KOIZUMI/Koizumi Studio|Domae and beyond

what truly matters is creating the desire to make

— Makoto Koizumi

photography : Koizumi Studio

words : Reiji Yamakura/IDREIT

In February 2025, Oitomi, a Nambu-tekki ironware workshop, opened a new location called "Domae" on a site adjacent to their main factory in southern Japan. The renovation design was undertaken by Makoto Koizumi of Koizumi Studio, who has a long-standing relationship with the company. We visited Koizumi at "Koizumi Doguten" (Koizumi Tool Shop) in Kunitachi, Tokyo, where he sells products he has designed, to discuss the spatial design of Domae and his unique approach to sharing ideas and intentions with craftspeople in production regions.

Oitomi, based in Mizusawa, Oshu City, Iwate Prefecture, is a historic Nambu ironware workshop founded in 1848. Koizumi has previously designed numerous products for the company, including teapots, and was consulted about the renovation.

"The project started when Mr. Kikuchi, the managing director of Oitomi, acquired an old single-story Japanese house adjacent to the main office," Koizumi recalled. "While there was already a showroom inside the main office, they wanted a space to welcome overseas guests, serving them tea across a counter. They also wanted part of it to serve as Mr. Kikuchi's residence, and we began developing the design ideas while listening to these requests."

The entrance, once an earthen-floor kitchen with a partial mezzanine, was transformed into a showroom and gallery, while the back living space with water facilities was tidied with minimal modifications. "Since the guest reception space was intended for new product launches, exhibitions, and occasional events like rakugo performances, we stripped the floor at the entrance and returned it to its original earthen configuration," Koizumi said.

The interior of Domae, the showroom and gallery of Oitomi, a Nambu-tekki ironware workshop. It features an original long table made from cedar timber.

The open-plan counter is situated in the earthen-floored area. A built-in bench can be seen along the left-hand wall.

As the client understood Koizumi's style, there were no specific design requests. The project progressed through shared models. What sets this renovation apart is the custom furniture and architectural hardware—like the table spanning the earthen and raised wooden floors and Nambu ironware elements crafted specifically for the project.

"The young carpenters found the detailed work interesting, so we involved them in the design," Koizumi explained. "For the table, high-quality cedar was available, so the top was designed to showcase the solid timber, with iron legs finished at Oitomi's workshop."

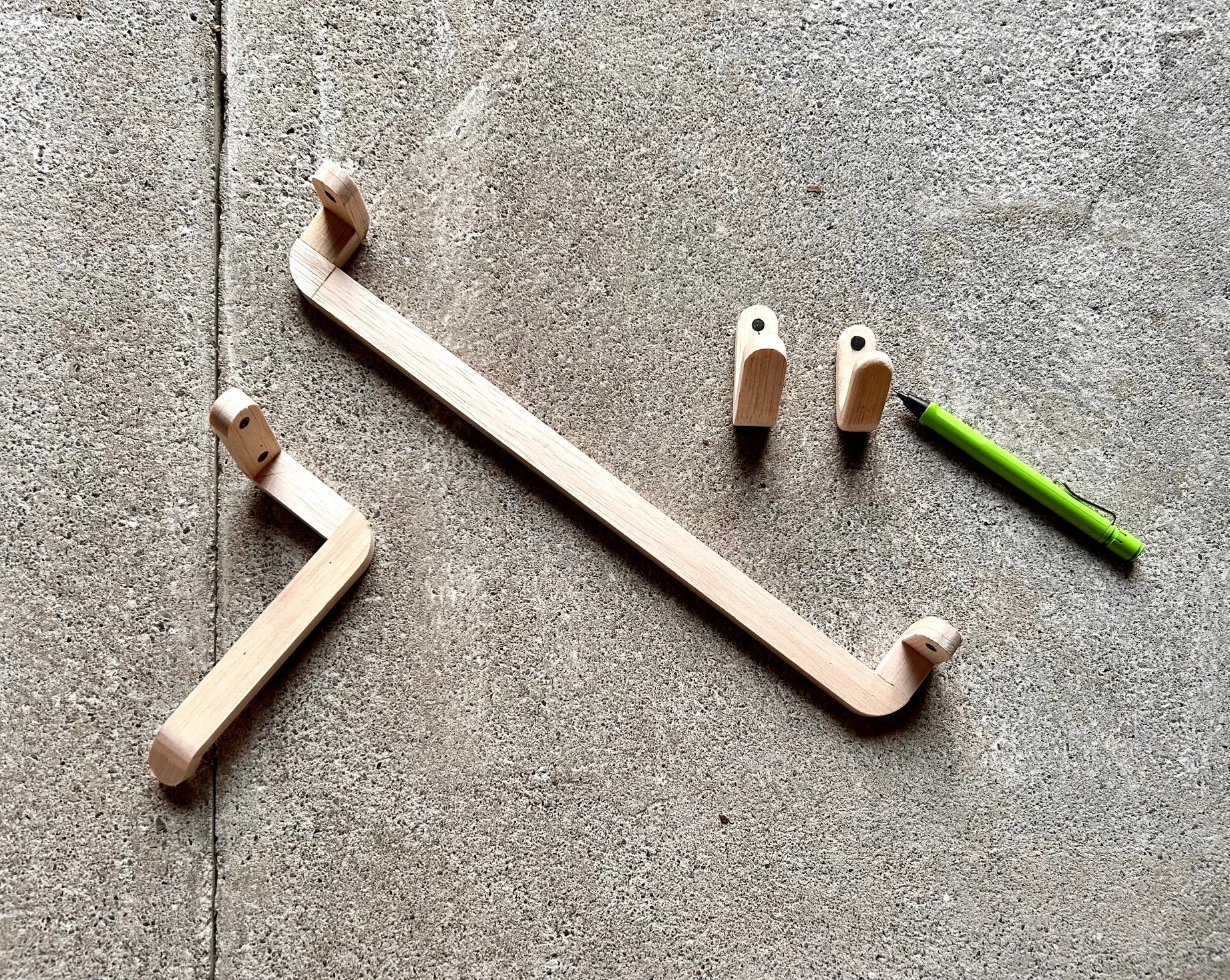

Koizumi first hand-crafted prototypes in wood, which he then used to develop Nambu ironware door handles, towel hangers, hooks, and toilet paper holders. The towel hanger can also serve as a door handle when positioned vertically. "All of these pieces were born from the needs of the space. It would be wonderful if they could be commercialized as Oitomi products," Koizumi said. These items utilize Oitomi's expertise in surface finishing, with safe, rust-resistant coatings complying with food sanitation laws. He carefully balanced the use of iron, applying it only at focal points to ensure comfort and usability.

Asked about the playful pendant lighting made from a teapot, Koizumi laughed: "I proposed a pendant made from a teapot with the bottom removed. Mr. Kikuchi loved it, so we made it." In the earthen floor area, there are also "TETSUBO chairs" with iron bar frames, which Koizumi designed for a previous Miyakonjo project in Miyazaki Prefecture.

Full-scale wooden prototypes crafted by designer Koizumi during the design process for the metalware.

Iron-made door handle. This handle can be used horizontally as a towel hanger.

A pendant light created by hollowing out the base of an iron pot and fitting a light bulb inside.

Koizumi’s approach remains consistent across products and spaces. "I question whether I can give 'meaning' to decoration. As a result, my designs always have only the necessary lines—something like an inevitable design."

He treats spaces and products without distinction. "Whether it's a house or furniture, everything is a tool for living. Over twenty years ago, I realized that in shoin-style architecture, Japanese people designed architectural elements and furnishings as a cohesive whole. Alcoves, shelves, and window niches were seamlessly built into the structure. That was when I came to see architecture itself as furniture."

From this perspective, some works naturally blur the line between furniture and space. Regardless of the medium, Koizumi says his work always falls into one of three categories.

"There are three kinds of design," he says. "The first sells quickly. The second gains public attention. The third sells slowly over time. I focus on the third. If a client wants the first two, I tell them I’m not the right person."

Success depends on the purpose behind the work. Those pursuing the first two often take a market-driven approach, rather than one guided by the maker’s hand.

As an example, Koizumi recalled a project where Oitomi commissioned him to design a cast-iron teapot.

"Before starting, I visited the workshop and observed molten iron being poured into sand moulds. I sketched while discussing ideas with the craftsmen, selecting and eliminating concepts as if playing a card game. Drawings alone make craftsmen focus only on technical aspects, but this approach revealed their honest reactions and what they wanted to create through continuous production."

Through this process, they developed tools using iron’s weight, like heavy tape cutters and thick bookends, instead of teapots. Koizumi emphasizes that creating truly good products requires shared passion between designer and maker—a relationship many designers struggle to achieve.

Koizumi shared insights gained from years of visiting production sites and working alongside manufacturers. “In today’s Japanese manufacturing, what truly matters is creating the desire to make. Craftspeople need to feel, ‘This will be fun to make,’ before they begin. Before shaping the form itself, it’s essential to cultivate that positive mindset within the maker. I’ve only recently come to truly understand this.”

Taisetsu Mokko, located in Asahikawa, Hokkaido, one of Japan's foremost furniture-producing regions.

One example is his collaboration with Taisetsu Mokko in Asahikawa. For the first ten years, little product design occurred. Koizumi met president Mr. Hasegawa in 2013, when the makers could not take pride in their work. Koizumi candidly said, “It won’t be easy, and it will take time.”

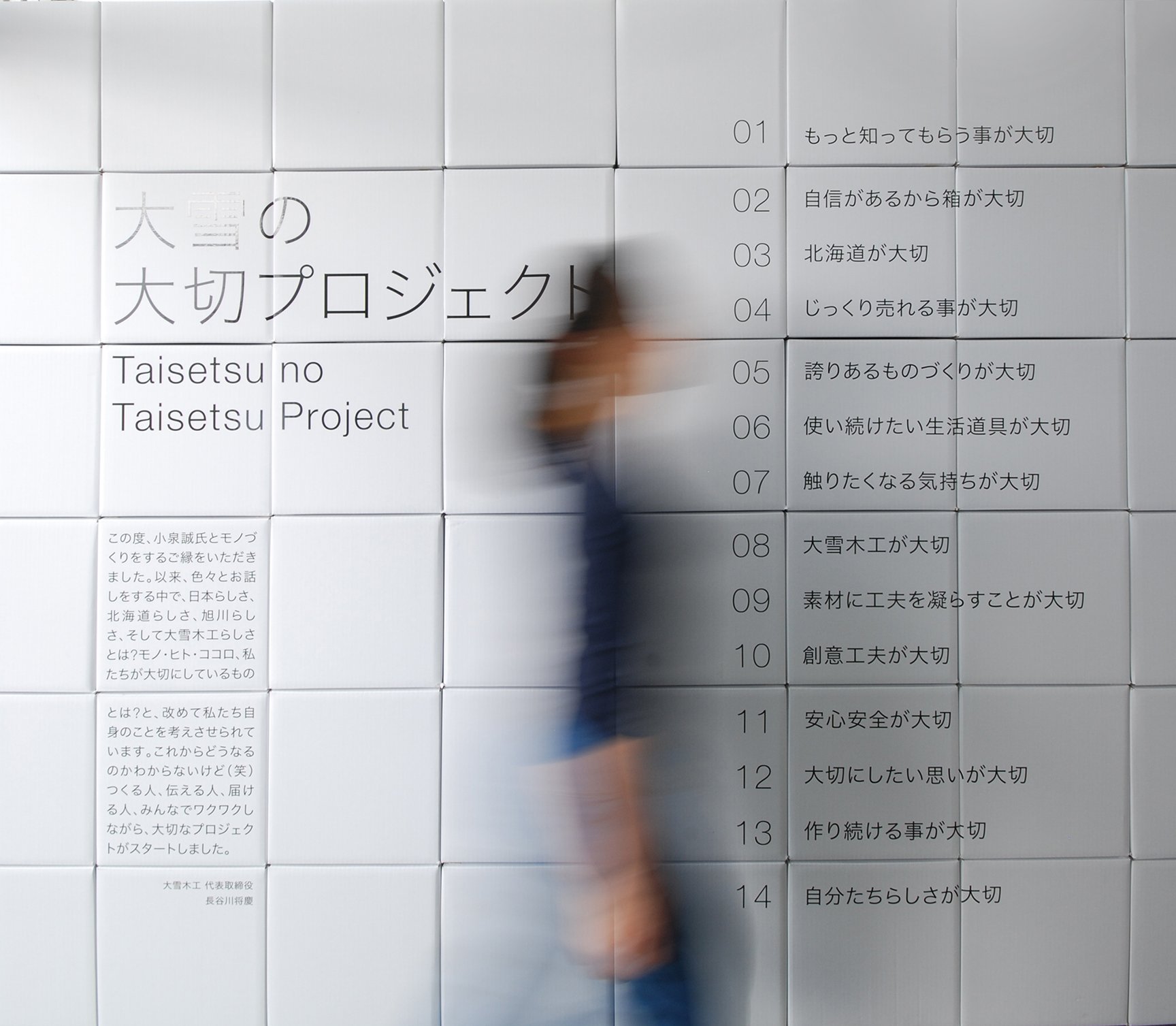

The president struggled for two years, visiting factories of other collaborators. After seeing them firsthand, he decided to move forward with us. Koizumi created a slogan and, with local graphic designers and coordinators, launched the “Taisetsu no Taisetsu Project.” Centered on Taisetsu—the Japanese word for “important things”—it explores what truly matters in creating meaningful objects.

The second year of the Taisetsu Mokko project in 2016, designed with white cardboard boxes.

Taisetsu Mokko's exhibition at the 2019 Asahikawa Design Week. Taking the box as their exhibition theme, they exhibited a unique product featuring a desk built into the box.

A series of box-shaped furniture pieces exhibited in 2019, designed for people to sit inside.

Initially, core employees and external members like Koizumi led discussions, while others observed. As the team started to see results little by little, showcasing the project at Asahikawa Design Week and carrying out partial renovations, employee awareness shifted. Employee-led voluntary workshops were started.

“Five years after the project began, young people wanted to join the company. In 2023, voices emerged within expressing a desire to create original products. From the moment I met the president, it took ten years to reach this point,” he explained. “Working alongside makers requires commitment for the designer, and cultivating their desire to create takes time and effort.”

Koizumi, now with relationships spanning 30 years, felt a strong urge to share these experiences with other makers.

The exhibition of “Taisetsu no Taisetsu Project” at the 2023 Asahikawa Design Week. The venue design is handled by Koizumi Studio each time.

Taisetsu Mokko's veneer warehouse. This vast space has occasionally been used as an exhibition venue since 2017.

At the end of the interview, we asked for a comment to young design students, he replied:

“The greatest joy in design is discovering new things for yourself. Teachers often give too much instruction, and I think that’s part of the problem. Because giving them all the answers would take away the real pleasure of discovery, I usually tell them, 'Try thinking for yourself.' Discoveries made through research or hands-on experience are the most enjoyable and useful. Learn the basics from others, but beyond that, explore on your own and truly feel the joy of design.”

Group photograph at Taisetsu Mokko.

Koizumi Studio continues to explore both spaces and objects. Among their recent projects is the renovation of Yuhokan Hida Gallery (grand opening October 4, 2025) in Hida Takayama, a collaboration with architect Yoshifumi Nakamura, who was also Koizumi’s mentor during his student days. The studio is also working on unique designs, such as cast-iron teapots in collaboration with Nambu-tekki ironware workshop Oitomi. With projects underway nationwide, we can look forward to their upcoming releases.

MAKOTO KOIZUMI

Furniture designer. Born in Tokyo in 1960, Makoto Koizumi trained in woodworking and worked under Choei and Shigemitsu Hara. He founded Koizumi Studio in 1990 and opened Koizumi Doguten in 2003. His work spans everything from architecture to small everyday objects, always with a focus on collaborating with local communities. In 2015, he launched Wazawaza, a project aimed at bringing traditional craftsmanship back into daily life. He is also an Honorary Professor at Musashino Art University and a Visiting Professor at Tama Art University.